The case for universal, public long-term care insurance: How social democrats should address the emerging home-care crisis

The current overreliance on family caregivers, mostly women, is emotionally burdensome, socially regressive, and economically counterproductive

This newsletter aims to help revive the political prospects of social democracy in an era unlike the period of its political dominance after World War II. After the war, social democrats successfully fought to have wage-earners share in the economic growth of market economies and they built strong welfare states, particularly in Europe, to support those who couldn’t work: children, people with disabilities, older adults, college students, and those temporarily unable to work due to illness, layoffs, and the like.

Today, advanced democracies are not seeing the strong economic growth of the postwar decades; some call it “secular stagnation.” Growth has been weak since the mid-1970s and while the professional and managerial classes have done well, the average worker has seen little or no growth in real wages. This same period has seen women entering the workforce in large numbers. Many want to pursue rewarding careers. All see it as necessary for ensuring a middle-class lifestyle for their families.

Unpaid family caregiving, a burden for women

While nearly all developed democracies have publicly-sponsored universal health coverage of one sort or another (the U.S., with a very large private market, is an exception), few countries offer universal long-term services and supports (LTSS) for older and younger disabled adults. Today, LTSS means primarily care at home, the least restrictive, most person-centered, and most preferred form of care for the vast majority.

Thus, while public health-insurance programs, including Medicare in the U.S., are obligated to spend huge sums treating cancer, renal disease, heart failure, COPD, and the like, if an older adult needs help at home with bathing, dressing, cooking, cleaning or other activities of daily living (ADLs), or needs close monitoring due to the ravages of dementia, she must often look elsewhere for support. This kind of care, variously called home care, personal care, or social care, is clearly related to health care, yet is typically kept separate and is rarely universal.

The largely unacknowledged reason for the separation is the persistent expectation that family members, mostly daughters or daughters-in-law, will step in to care for their aging parents and other relatives often while still providing support for their own children. Yet, to mitigate costs, most governments structure long-term care programs to encourage and maximize the unpaid services of family caregivers, a regressive social policy.

While many nations provide means-tested formal caregiving support for the poor, working and middle-class individuals who are not poor enough to qualify for support, but who cannot afford to pay out of pocket for assistance, are often faced with living unsafely at home, being forced into an institution, or self-impoverishing to qualify for means-tested support. Younger adults with disabilities, who need care for a lifetime, are especially impacted by means-testing. They turn down good jobs and promotions, and forego higher education in order to remain poor enough to qualify for an aide and avoid institutionalization.

Family caregivers, in turn, may quit jobs or reduce work hours to care for an older relative, and usually during their peak earning years.

These many millions of older and younger adults with disabilities, and their unpaid family caregivers, are a natural constituency for social-democratic parties and political factions. The central political message? Any adult needing assistance with any ADLs should be offered formal caregiving in their home, as a universal healthcare benefit. Family caregivers may continue to be involved, of course, but as a matter of choice.

The 2030 caregiving crisis: worsening shortages of formal and informal caregivers

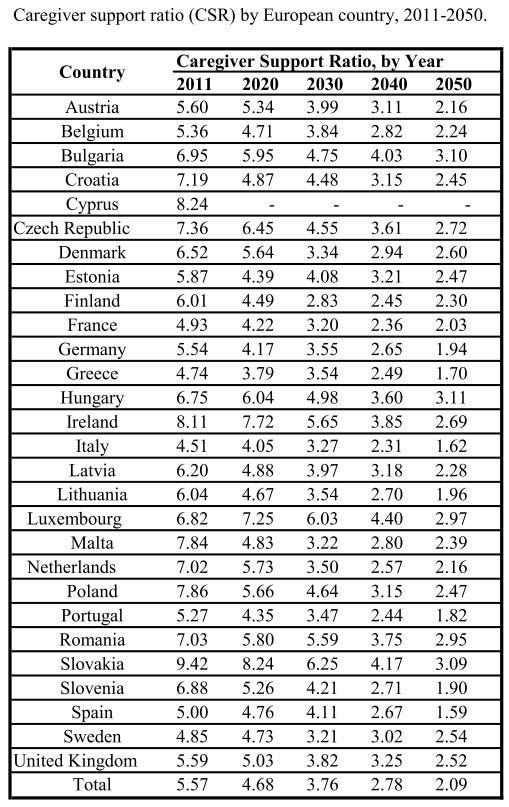

The caregiving situation is rapidly gaining urgency. Demand for home care will skyrocket through the 2030s and 40s as members of the huge postwar boomer generation become the oldest old (80+ years). Yet, the “birth dearth” that followed the boomers and more recent birth rate decline guarantee that the caregiver support ratio (CSR) of potential family caregivers in the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries will drop by over 50% in 2050 from the number available in 2010. The CSR is the number of potential caregivers aged 45 - 64 years for each person aged 80+.

To keep boomers out of nursing homes, then, the obvious top priority will be to recruit and train millions of paid home-care workers to both close the growing gap and replace unpaid care where needed.

Yet, despite the need and demand, home-care worker shortages are growing rapidly across all nations. While home-care aides find the work generally gratifying, recruitment is difficult under current conditions of poor pay, benefits, and working conditions, and a growing cash-based “gray” market that pays even less. In addition, injury, burnout, and turnover rates for home care aides are higher than those of nearly all other occupations and there are few opportunities for career advancement. Language deficits and recent strong opposition to immigration and immigration reform have cut even further into the potential to build the needed home-care workforce.

There are further factors that serve to amplify the crisis:

Boomers are not that healthy: High hopes for a “compression of disability” due to healthier last years of life have proven overly optimistic. The lifetime effects of obesity, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and inflammatory conditions are expected to keep the incidence of dementia, mobility disorders, and frailty at high levels. The prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease, for example, is expected to double across the OECD between 2020 and 2050. Ironically, advances in medical technology, specialized surgery, and drugs that have reduced early deaths, have also allowed more to live into their 80s and 90s, when disability incidence and prevalence increase dramatically.

Boomers are not that wealthy: Real-wage stagnation since the 1970s and the long climb out of the Great Recession have seriously impacted retirement savings for the lower quartiles of boomers. 45% of boomers in the U.S. reported no retirement savings. Pensions in the EU have not kept up with inflation and are being subjected to cost-saving “reforms.” Aging boomers will not have the resources needed to contribute to their long-term care.

Many boomer children will be worse off economically than their parents: While there are Millennial and Gen X urban professionals who are doing quite well, the bottom half of those generations were also hit hard by inequality and the Great Recession and are struggling financially. They will not be able to contribute much to the care of their parents, either financially or in terms of time spent away from work.

Intensive caregiving and emotional burden: Dementia incidence and prevalence will skyrocket over coming decades. Caring for those with moderate to advanced dementia involves addressing a wide range of troubling behavioral disorders requiring, by far, the most intensive and burdensome type of care. Rates of family caregiver depression and anxiety disorders are far higher among those caring for family members with dementia.

We have then a perfect storm combining prevailing real-wage stagnation, changing labor conditions, and worrisome demographics.

Addressing the crisis: Cost is not a barrier

Most government leaders are duly concerned about prospects for their most vulnerable residents. They further recognize that most are adamantly opposed to entering nursing homes, even good ones, unless they absolutely must, especially in light of the Covid nursing home catastrophe. They further recognize that most can’t afford private long-term care insurance or to pay much out of pocket for their care.

Yet, these same leaders plead that they can’t possibly afford to provide a universal home-care benefit. Even those nations that have a universal program on paper, mostly in Northern Europe, readily admit that they rely on unpaid family caregiving and nursing homes to provide the bulk of personal care for those needing assistance with ADLs. They pursue policies that support and encourage family care, including respite services, extended family leave, tax breaks, and small cash stipends.

They sometimes create circumstances where family members and friends are literally forced into providing care. One such insidious approach is to limit caregiving hours. An older adult might be awake and hungry for breakfast at 5AM, but relegated to lying in bed, perhaps in soiled diapers, until a scheduled aide shows up at 8AM. Family members must often fill in the gap since 12-hour or round-the-clock care is rarely offered. There are many such stories that can be told.

Another approach involves limiting the type of care. Housekeeping, for example, might not be included in a care plan, forcing an older adult on a fixed income to hire helpers or for family members to fill in. A number of nations have begun restricting hours and types of care.

There are two main cost issues that worry government policymakers. The first is sometimes called “woodwork effects”, the expectation that too many unpaid caregivers would drop their care commitments should a universal cost-free or inexpensive home-care benefit be introduced. The second involves the costs associated with recruiting and training the many millions of home-care aides that are, and will be, needed to provide care for all, including round-the-clock care.

But is cost really the problem? A closer look shows that it may be more costly to do nothing or not enough to address the crisis. There are four reasons why a truly universal home-care program could be established at a reasonable cost to taxpayers and care recipients: 1- Home care is less expensive than institutional care; 2- Woodwork effects will likely be modest; 3- Potential family caregivers would remain productively employed; and 4- Investing in building a well-paid home-care workforce will reduce poverty, support immigrant communities, and have a positive impact on the general economy.

Home care is less expensive than institutional care

Although it is difficult to estimate the cost difference between institutional and home care, most experts agree that delaying or bypassing institutional care reduces long-term care expenses for individuals and families, and creates savings for governments.

In addition, studies have shown that medical expenses for older adults living in their homes average less than expenses for similarly-characterized individuals in institutions. This is partly due to lower levels of stress, depression, and anxiety disorders. It is well-known that stress and poor mental health can impact physical health. It is also partly attributed to the lower likelihood of acquiring an infectious disease like influenza and pneumonia, not to mention Covid-19.

While reduced lifespan for those in nursing homes may offset some of the expense differential, over time even small differences will add up to large differences in cost, and no one wants to address the crisis by reducing the time to death of loved ones.

Woodwork effects will be modest

In 1998, Scotland introduced a universal, cost-free, long-term care benefit. Anyone at any income level could automatically qualify for home-care services at no cost. Up until then, as in most European nations, unpaid family caregivers and institutions provided the largest component of care services.

To prepare for what they thought would be a sharp uptake of the benefit and a decline in unpaid care, the government set aside a fund to handle the expected increased cost. The fund initially went unused. Family caregivers continued to provide significant hours of care and paid caregivers, if used, were largely deployed to handle the most burdensome care, or care needed to allow the family member to keep a job or attend school. In addition, many care recipients resisted having a care worker enter their home under any circumstances. Over time, the cost of the program rose, but only incrementally, partly due to a shortage of home-care workers.

In the U.S. several studies have shown that only about 50% of those receiving unpaid care would opt in to a paid formal program.

Potential family caregivers would remain productively employed

The adult children of older adults are the primary providers of unpaid care, as noted above, and they must often leave employment or reduce hours in order to care for a relative and usually during peak earning years. This represents lost spending in the general economy, lost tax revenue, lost productivity for companies, and a reduction in labor force skill levels.

European long-term care systems rely heavily on unpaid family caregivers. While these nations offer more generous family leave benefits and other supports for caregivers, there are still losses to the general economy when peak earners must leave the workforce.

Investing in building a well-paid home-care workforce will reduce poverty, support immigrant communities, and have a positive impact on the general economy

All nations are facing significant shortages of home-care workers which will get much worse unless significant progress is made in recruiting and training the many tens of millions who will be needed to handle the increased need and to replace workers leaving the field. If we are serious about keeping adults out of institutions and committed to reducing the burden on unpaid family caregivers, then there is really no alternative to improving the pay, benefits, and working conditions of formal home-care workers.

A recent study of the New York State workforce estimated that about one million new workers would be needed in the state over the next ten years and that it would take increasing the starting salary of workers by 150% over their current minimum wage to recruit and retain workers who would otherwise seek other jobs. While the increase would cost the state billions, the positive economic impact, according to the study, would be greater than the amount spent. The increase would reduce worker need for public assistance benefits, increase state income tax revenue, increase consumer spending and sales tax receipts, and improve workforce productivity by reducing burnout and turnover.

Not included in their estimate was the expected reduction in ER visits and hospitalizations that would result from better care. Also not included were the improved financial circumstances for caregiving families as described above.

Long-term care and social democracy

Current long-term care systems in the advanced democracies are not up to the task of addressing the emerging caregiving crisis. As the crisis deepens, the burdens on unpaid family caregivers will increase and the positive recent shifts from institutional care to home care will end. Women caregivers will bear the brunt of this socially regressive situation as they assume the emotional burden of caring for relatives, especially loved ones suffering from dementia. They will also be the ones who lose income, forego promotions, and abandon desirable careers.

Current systems also undervalue the role of care workers, mostly women of color and recent immigrants, by paying them below their social worth. Their official pay is bad enough, but they are also victimized by those who take advantage of their desperation and illegally pay them cut-rate wages in cash on the gray labor market. Yet, they, too, have families to support. Immigrants will constitute a primary pool from which care workers will be recruited over the coming years which will mean overcoming bias, ending abuse, and treating them as respected paraprofessional members of the healthcare team.

Social democrats understand that society must support those who cannot work. They know that health care is not a commodity and that markets cannot address the emerging caregiving crisis. European social-democratic parties, in particular, have a long and impressive record of enacting universal social welfare and social insurance programs that promote fairness and solidarity.

The emerging crisis in the caring economy has created a situation where social democrats can reassert their values and revive their electoral prospects. Nearly every voter is giving or financially supporting care, receiving care, will soon be giving or receiving care, or has a friend or family member in this same situation. Social democrats must declare that, while wage-earners are willing to pay their fair share, it is the responsibility of the state, businesses, and society as a whole, to support those who cannot support themselves.